Language is a Human Right, Not an Accommodation

A graphic and Ideas for Progress Contribution by Amanda Avilla

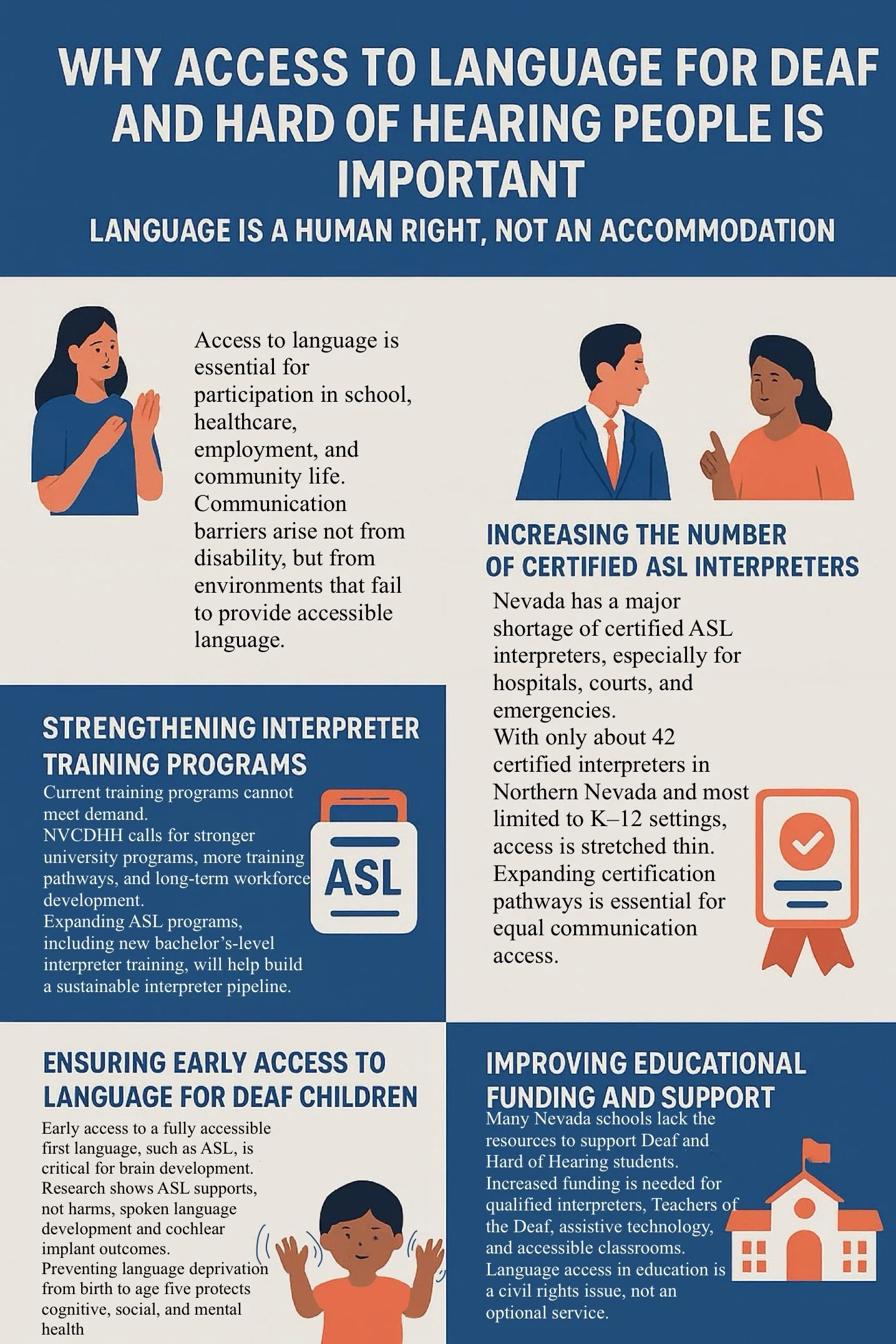

Clear communication can mean the difference between opportunity and exclusion. Northern Nevada's Deaf and Hard of Hearing community continues to push for a fundamental necessity: access to qualified American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters. In classrooms, hospitals, and workplaces across Nevada, thousands of Deaf and Hard of Hearing residents navigate daily life with one persistent barrier, access to communication.

For Deaf and Hard of Hearing people, the presence of a qualified American Sign Language interpreter or a language-rich classroom is not a convenience, it is a necessity. A language-rich classroom is one where Deaf and Hard of Hearing students have full access to communication all day long. This typically includes fluent or intermediate ASL users, visual learning strategies, direct instruction in ASL, and opportunities for natural back-and-forth communication. Without this kind of environment, children risk language deprivation, delayed development, and long-term educational barriers. It is the foundation for full participation in society. Barriers do not come from deafness itself; they come from environments that fail to communicate in accessible ways.

Nevada’s Reality: A State Without a Deaf School

Nevada is one of the three states in the U.S. without an established deaf and blind school. Instead every Deaf and Hard of Hearing student is placed in a general education classroom. Many of these classrooms are barely equipped to support them because the state faces a severe shortage of qualified interpreters.

Schools often rely on Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) which is a zoom video call where an ASL interpreter is in a cubicle that can be thousands of miles away from the classroom interpreting for the teacher. In theory it’s a solution; in practice it collapses instantly. Teachers move around the room. Students talk from different corners. Microphones cut in and out. A Deaf student sitting in front of an iPad can miss half the lesson simply because the teacher stepped out of frame. VRI becomes a crutch, not a support, attempting to cover a shortage too large for technology to fix. This is still a barrier with a bandaid plastered over the severe shortage.

The Commission Sounds the Alarm

Recognizing the seriousness of the issue, the Nevada Commission for Persons Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing (NVCDHH) recently issued new position statements calling for urgent action. Since its establishment in 2007, the Commission has worked to ensure equal access for Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, DeafPlus, and speech-impaired Nevadans. Its latest recommendations push for expanded interpreter access, stronger educational systems, and early intervention to prevent language deprivation before it begins.

Interpreter Access: The First Barrier

Nevada’s interpreter shortage is at the center of almost every communication barrier in the state. Northern Nevada has roughly forty-two certified interpreters, and most of them are stretched across K-12 school placements. Only a handful have the higher-level certifications required for hospitals, emergency departments, and legal settings. Nationally, the ratio of of certified interpreters to Deaf individuals is already an alarming one to fifty with Nevada’s numbers fall even lower.

The need isn’t just for more interpreters but for better pathways to train them. At the University of Nevada, Reno, the ASL minor offers a strong foundation in language, service learning, and Deaf culture, but it stops short of preparing students for interpreting careers. Those who want to pursue certification must leave Northern Nevada entirely. Nevada State University, located near Las Vegas, is the only institution offering a full interpreter preparation program, leaving most of the state’s future interpreters without accessible options. When students must leave to train, many do not return which intensifies the regional shortage.

Early Language Access: Preventing Harm Before It Happens

For Deaf children, early access to a fully accessible first language is not optional; it is essential to their development. Research, including Wyatte C. Hall’s work published in the Maternal and Child Health Journal in 2017 shows that exposure to ASL from birth does not interfere with spoken language acquisition. In many cases, it actually strengthens outcomes for children with cochlear implants and supports language development that parallels their hearing peers.

When Deaf children go without accessible communication during their critical early years (birth to age five), the effects can be permanent. Studies link early language deprivation to delayed cognitive development, reduced academic readiness, and even long-term mental health challenges. Bilingual exposure, sign language alongside spoken language, is consistently shown to produce stronger outcomes than speech-only approaches.

NVCDHH stresses that language deprivation is entirely preventable, but only if the state prioritizes early access.

The Human Impact: My Story

My name is Amanda Avilla and I’m Hard of Hearing. I was born with my hearing loss, but because of a bunch of family circumstances, I didn’t actually find out my diagnosis until middle school. Looking back, there were so many signs, but since I still had some hearing and because my siblings had their own learning differences, everyone assumed my struggles were just the same thing happening again.

By fifth grade, I was at a second-grade reading level. I constantly fell behind in anything involving reading or writing, and this honestly crushed me. I felt stupid. I couldn’t spell basic words like “accept”, “business”, or “possibly.” I kept thinking something was wrong with me. Like maybe I was just incapable of learning the way everyone else could.

My grades continued to slip, and no one really knew what to do. I got tested for learning disabilities over and over again, but never scored “bad enough” for anyone to actually do anything. So instead, I spent hours in the counselor’s office, flipping through flash cards, taking endless assessments, and sitting under that awful pity-stare adults do when they think you’re “trying your best.” Every test felt like another layer of weight on my shoulders.

A teacher finally recommended testing through UNR’s learning and development center. That was the first time someone recognized I had a moderate to severe cookie-bite hearing loss. But even then, the diagnosis wasn’t “official,” so I spent the next year being pulled out of class for eight more tests across Reno and Truckee. I was so exhausted that I started memorizing the fifty words they used for every exam just to get through them faster. Eventually a brain scan confirmed what the very first test had already detected.

And even then the fight wasn’t over. I had to sit through yearly meetings explaining to adults, teachers, administrators, and eventually college professors, why I needed basic accommodations like captions. Many meetings weren’t attended by the teachers who needed to be there. Even at the university level, I’ve had professors push back on providing captioned materials.

Every day, I navigate a world built for people who hear differently than I do. I still have anxiety about losing the rest of my hearing. It’s why I learned ASL and why researching language access in Nevada hit me so deeply. I know what it feels like to grow up without the communication support you need. I know the isolation, the frustration, and the silent ways a lack of access chips away at confidence.

And I’m not the only one.

Looking Ahead: Signs of Change

Despite the challenges, there is movement. Organizations like Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD) Works Nevada are actively rebuilding resources for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community. From offering ASL classes and Deaf mentoring to restoring access services and distributing equipment, these programs are helping stabilize support systems across Northern Nevada.

Combined with expanded interpreter training, early language access, and stronger educational funding, these efforts point toward a future where language access is seen not as an accommodation but as a fundamental human right.

Nevada has the opportunity to build this future.The question is whether the state will act fast enough, because communication isn’t a luxury for Deaf and Hard of Hearing people. It’s everything.

Feel free to share this Ideas for Progress contribution on these social media platforms: