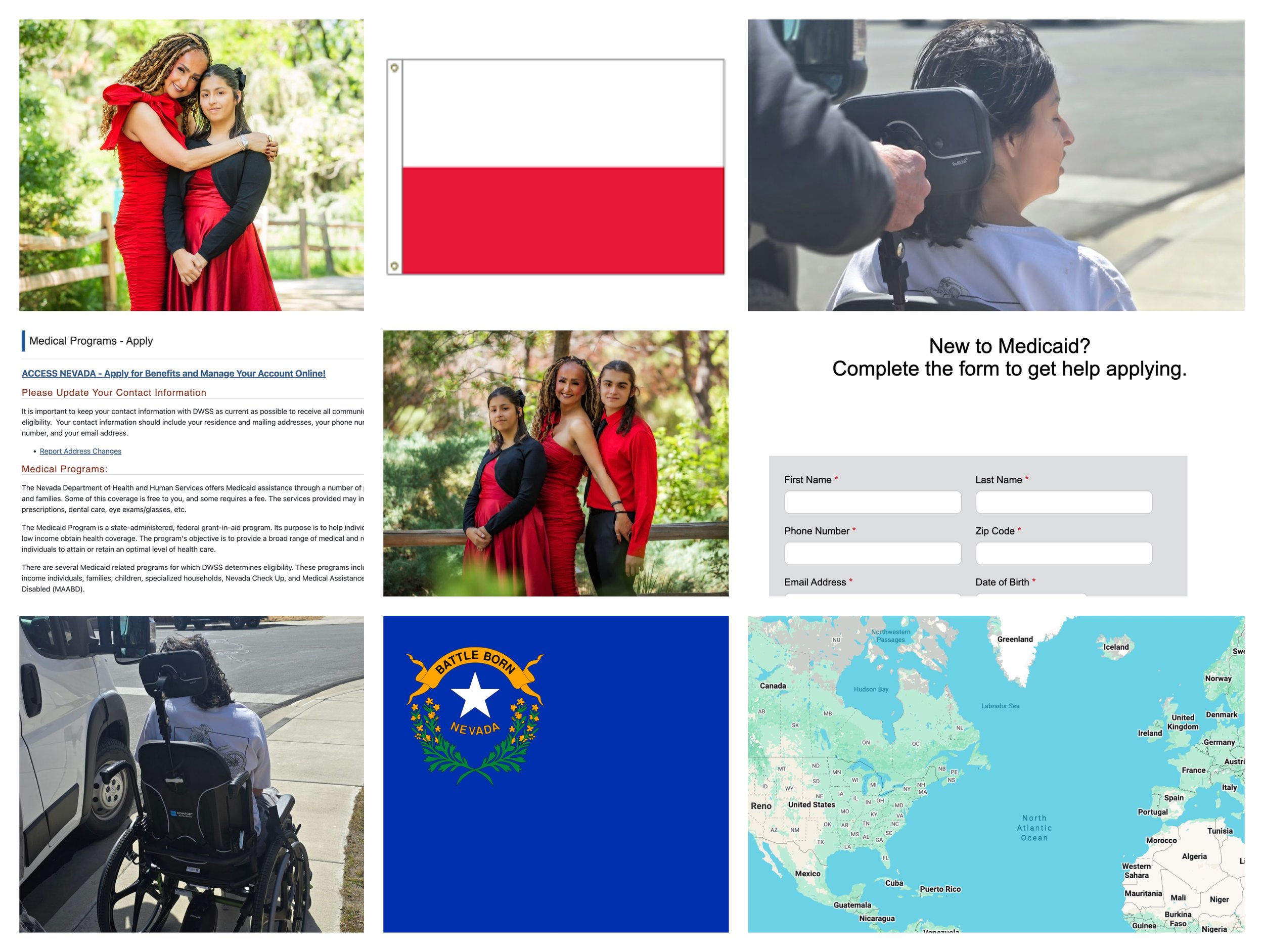

Izabela Kropiowska (center) and her children Anna (left) and Stanislaw Kropiowska (right) pose in center photo. Anna was diagnosed with both Ullrich Congenital Muscular Dystrophy and Fukuyama Congenital Muscular Dystrophy before she was two, while being deemed profoundly deaf at the age of three and a half. Photos provided by the Kropiowskas with reporting by Stella Kraus and Kelsea Frobes.

“I’m gonna die fighting for my daughter and every child in between,” says Reno resident Izabela Kropiowska, the mother of 14-year-old Anna Kropiowska. They regularly go back to Poland to seek out accessible and affordable care.

Despite the challenges and costs of these long trips, this choice makes sense for the Kropiowska family due to the even higher costs and difficulties of getting help here, with long waits, provider shortages, and a complex and underfunded system to navigate.

Even with their repeated travel, the Kropiowskas sometimes have no choice though but to deal with some of the financial stresses of our local system.

For example, Anna’s electric wheelchair isn’t covered by insurance. Her mother, who works seven days a week at a Sephora to support her family, says she had to put that payment on her credit card.

A local disability case worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said without a state income tax in Nevada it limits the state’s available revenue to fund public health programs, exacerbating the reliance on limited Medicaid funding.

“The waitlists are long because there simply isn’t enough funding to match the need,” the case worker said, with fears of even steeper cuts and staffing shortages ahead amid the current political climate.

Families report waiting months, sometimes years, for essential services such as occupational therapy, speech therapy, Medicaid waivers, or at-home support. Case workers describe turning people away, not because they don’t qualify, but because no provider has availability.

Costs can also be too steep. Kropiowska says that her daughter’s disability insurance was taken away at the beginning of this year as she now makes just $11 over the limit to qualify.

For Kropiowska, despite the hassle of travel, seeking treatment in Poland is cheaper and more comprehensive. She explains that care for her daughter in Poland is coordinated across doctors, physical therapists and specialists who work together in a cohesive and helpful way. Kropiowska’s parents are physicians which gives them an inside track to make sure their granddaughter is well taken care of whenever she visits.

According to international expenditure data compiled by the Social Security Administration, using OECD comparisons, a study from 2007 to 2013 indicated the US spent just 1.4% of its gross domestic product on disability programs compared to over three percent in much of Europe, and nearly five percent in Scandinavian countries.

Even for a procedure such as programming Anna’s cochlear implants, the Kropiowskas went to Poland, where patients can receive the surgery and programming free of charge through state-funded programs, compared to the high costs and referral barriers found here in Nevada.

For other parents with children with disabilities, getting care doesn’t involve going international but it does involve leaving the Silver State.

A northern Nevada mom who asked not to be identified said she made the difficult decision to move one of her 22-year-old twins, who has severe autism, to Pennsylvania so he could attend a program not available here in Nevada. She said the program provides comprehensive, professionally supported services for neurodiverse adults aimed at developing independence and life skills.

For families, time is the most precious resource, and also the most wasted within our state’s health care system, according to Izabela Kropiowska. “Our children are a burden, they are not an asset,” she says, describing her experience with how the U.S. views children with disabilities.

As debates rage about the need to better fund disability care, and why some states including Nevada fall behind others, parents continue to make difficult choices, to move, wait, or leave the country to get proper help.

“I work my ass off and my child cannot get access to the stuff she absolutely needs. Riddle me that,” Kropiowska says.

Despite the health care barriers, Kropiowska says she is thankful for other experiences her kids are getting here, including their education at Excel Christian School, from which her oldest child, Stanislaw, is set to graduate from this year at 16.

Feel free to share this story on the below social media: